Soul warrior: Adnan Sarwar, soldier to writer

March 4 2014

Prize-winning author is a former Lance Corporal in the British Army…

IT is 2003 and Adnan Sarwar is in Iraq in a ditch, in the service of Queen and country, as a Royal Engineer soldier and wondering if he’ll ever make it out alive.

Around his camp, bombs fall nightly and no one quite knows what the next day might bring.

To this end, the 25-year-old, who has no experience of writing, has started to pen a diary about his experiences.

It’s a bit rough and ready, but Sarwar, now 35, wants it to be an honest and frank account, and as a British soldier who happens to be Muslim, he’s a rare sort.

In January this year, Sarwar won the Bodley Head “Financial Times” Essay award, topping more than two hundred entries from around the world and winning the respect and admiration of some heavyweight judges (among them Stuart Williams, publishing director of Bodley Head, a publishing firm).

His award-winning “British Muslim Soldier” essay is light and easy to read – but tackles profound questions, especially around the theme of identity.

Not bad for a Burnley boy who had a chequered schooling and had joined the Army full-time in 2000 – seeing service in Iraq, just three years later.

“I was 25, and I had never been in a war and I thought I might die…it was the only medium I had along with some pictures – the writing isn’t good – it’s all right, it gets the point across,” he told www.orangered-oyster-271411.hostingersite.com about his venture into writing and those early drafts.

But it was the start of something – a turning point perhaps for Sarwar, the writer.

Last year, he wanted to enter the same competition, hoping his diary would provide the essential material.

It did – and more, a few thousand words turned to nearly 50,000 – past the word count limit for entries and past the deadline and suddenly it seemed like he was onto something – the way a scientist is with a discovery.

“I wouldn’t come out of my room, I kept working on it and working on it, drafting and redrafting and it became 80,000 words.”

He has an agent and several publishers now considering this untitled work and is actively working on a second.

It’s a remarkable journey – one that is part of history in so many ways but for us (as a community), it is also about much more: racism, religion, identity.

Sarwar writes vividly about all three, but what is perhaps most remarkable of all, is his attitude towards the British Army.

There is no bitterness or unhappiness – he loved his time in the Royal Engineers, still misses it and reserves a huge amount of affection and loyalty for his former employer.

It is not that hard to explain and confounds many people’s rather limited expectations.

“I had more racial bullying in school than I ever did in 10 years in the military,” he explained.

“My Sergeant Major said to me: ‘You speak Arabic, don’t you? I said ‘No.’ He said: ‘Why not?’ I replied: ‘Because I am from Burnley.’

His schooling was tough – he was thrown into one where the majority were white and deprived.

His parents, who owned a shop, couldn’t emphasise the importance of education enough.

“Like all Asian parents they wanted us (Sarwar and his siblings) to be doctors or lawyers, but we got involved in extra-curricular activities such as gangs.

“There was a lot of stuff going on. The teachers tried their best, and I was excelling at things like and English and drama – but I wasn’t concentrating on those because I was trying to become a doctor.”

It meant Sarwar left behind the subjects he was good at and struggled through sixth form doing biology, chemistry and maths, hoping still to get the A levels to go to medical school.

His results were not good enough, but he managed to “wangle” (his words) his way onto a chemistry degree at Lancaster University where his deficiencies in the subject only became ever more apparent.

“It was awful,” he recounted. “And by that time I was in the Territorial Army (TA) and spending more time there than at university.”

At college some time earlier, a Royal Marines officer had come to chat to pupils about a life in the Army.

“I thought ‘wow’ this guy who has a really good life and is getting paid to do it and I thought I wanted to be doing something like that.”

He joined the TA and more or less immediately people assumed he would face aggression and racism.

“People were telling me that I was going to get my head kicked in – and it really upset me – once I’d joined nobody would do that to me. It wound me up.”

He was a practising Muslim – praying five times a days and observing spiritual obligations during Ramadan and Eid.

Rather than hostility, he encountered curiosity among his fellow soldiers and the army authorities were accommodating and respectful of his beliefs.

“There were a lot of people asking about Muslims and Pakistan and I could talk to them. I enjoyed the mixing.”

He thought he had found his vocation and never looked back.

“I loved it and got obsessive about it, even just ironing the uniform – all the little details.”

It’s clear he took a lot from the camaraderie and that from his own experiences he felt equal and valued in the army and not simply because it was what the authorities deigned as (politically) correct.

“I did feel comfortable because I am quite an expressive man and I liked the story of who I am and what I am and as they wondered about me and I wondered about them.

“You tell somebody the complete truth about yourself and they will tell you the complete truth about themselves.

“They have the same fears, the same loves. The guys were just inquisitive. You can have brotherhood with anyone.”

After September 11 and 2001, there was only more curiosity from his fellow soldiers.

He never felt different or alien and when in 2003, he was among the first soldiers to roll into Iraq with US forces, his faith seemed to some more of an advantage than a hindrance.

“My Sergeant Major said to me: ‘You speak Arabic, don’t you? I said ‘No.’ He said: ‘Why not?’ I replied: ‘Because I am from Burnley’.”

Nevertheless with the help of US Marine and Royal Navy guides, he was able to pick up the basics and was tasked with liaising with the locals and was responsible for the physical fitness of troops.

He ended up serving two terms in Iraq, one at the beginning of the war and then in 2006/07 as western forces began to pull out. He never made it to Afghanistan though he was keen to go.

Sarwar describes the later period in Iraq, as being much worse than his first in 2003, as British and US forces were located in one area and therefore far more of a sitting target than earlier.

Back at home in Burnley there were mixed reactions to his army role.

“Most people didn’t want to get involved – but some people did kick off, saying ‘Why are you killing Muslims?’ But they didn’t understand the conflict – previously to the Americans and British and coalition forces going in, Saddam was killing Muslims every day, thank you very much.”

He tried to engage with his critics but most were not interested in listening and only wanted him to agree with their interpretation of the “wicked West”.

He left the army at the end of 2007 with no distinct plan but wanted to see how he could cope with life on ‘Civvy Street’.

Training as a bodyguard and through personal contacts he nurtured on leaving, he soon became a consultant for TV and film companies wanting to utilise his experience as the real deal and he also worked as a columnist for a US-centred publication (“Taki’s Magazine”).

He started to write more seriously, did a Masters in filmmaking and has tried his hand at acting and has already been in one production and wants to do more.

Tall, smart and highly personable, he talks with great passion and conviction about writing and art.

He is a voracious reader and is in some ways trying to make up for the gaps in a ‘middle-class English liberal arts education’ and he certainly gives the impression he’s going places; Rilke, the ancient Chinese poets and Latin are more likely to feature in his conversation today, than snipers and bombs.

Sarwar writes with great insight and intelligence about some complex and difficult issues and what really appeals is his fresh, direct and very personal take on these subjects.

There are those who want the world to be black and white – about ‘them and us’, about ‘Muslims and the rest’ – but writers such as Sarwar show the world is not like that, and try to make us see and appreciate the world and its complexities. Labels are often lazy and miss the mark.

“I am not trying to write with any kind of political agenda but just write – this is actually the truth of what happened that day, if you’re going to have an opinion about the Iraq War, here, read an account from somebody who was there.”

Let’s hope a publisher understands why his story needs to be told and out there – because there are simply not enough counter-narratives to the ones that promulgate a ‘them and us’ belief system (especially, beyond the West) – and that history is just as much about soldiers like Sarwar as it is about leaders, Tony Blair and George Bush and weapons of mass destruction.

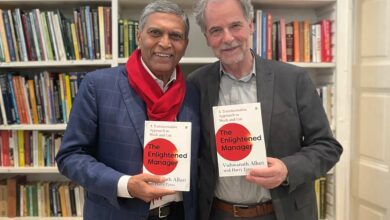

Picture: HRH Prince Charles meets Adnan Sarwar at a function for serving and ex-soldiers