Sex at the edge: dance bars and courtesans

January 8 2014

New book examines hidden worlds and their cultural connections…

IN 2005, the infamous dance bars of Mumbai were shut down, despite a wave of protests mounted by many of the dancers themselves.

Associated with prostitution, lewd behaviour and seemingly connected to an underground world of drugs and crime, the local politicians won their battle against sleaze and depravity as they choose to paint it. There was no nudity in these dance bars, and the girls danced in traditional clothes and they were not allowed to be touched, only admired.

Fast foward to 2013 and the ban was finally overturned by India’s Supreme Court and some of the bars look set to return and are currently going through a regulatory process.

The judge in the Supreme Court case is reported to have said that the ‘cure’ had been worse than the ‘disease’ itself, when he upheld an appeal by those who had opposed the ban in the first place.

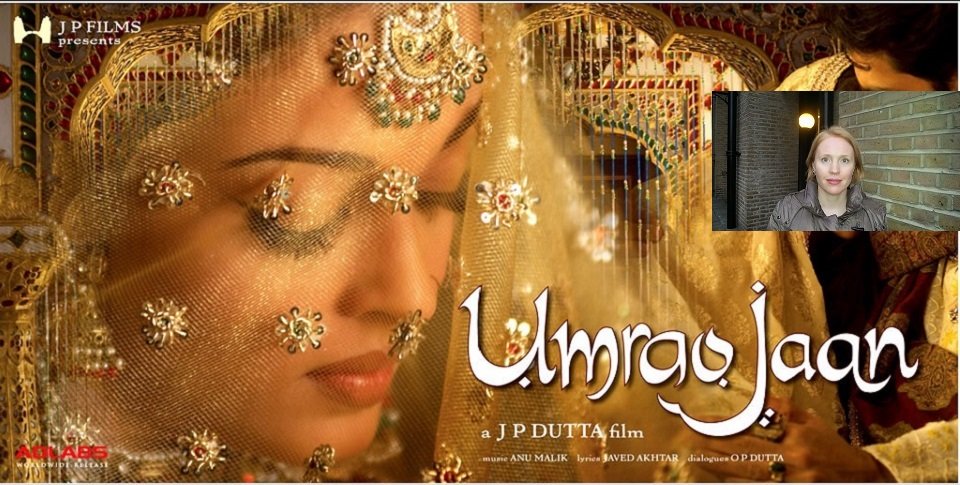

A new book, “Illicit Worlds of Indian Dance”, by British academic Anna Morcom (pictured inset), explores the cultural background, not just to the dance bars of Mumbai, but many forms of ‘entertainment’ that have existed within Indian culture for centuries.

In the book, she traces a clear line between the old courtesan (tawaif) system, supported and patronised by a wealthy and often regal elite, to their modern versions.

“When I went to Mumbai to find out about the dance bar girls, their leader told me that most of the bar girls were hereditary dancers or performers and I was completely gobsmacked,” she told www.orangered-oyster-271411.hostingersite.com.

“These were the very same communities the courtesans were from,” added Morcom, who studied Hindi and Ethnomusicology at the School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS) and speaks fluent Hindi, as well as being able to read it. She has also written a book about Hindi film songs and has also published a book on Tibetan music, all inspired by a gap year out in India and teaching then at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts in Dharamsala.

The courtesans, she writes about, have been often celebrated in popular culture – in such films as “Pakeezah” (1972), “Devdas” (2002), and “Umrao Jaan” (2006) (main picture).

There are also reports that the latest Farah Khan blockbuster “Happy New Year” scheduled for a Diwali 2014 release, features a dance bar girl in the form of superstar Deepika Padukone.

In her book, Morcom also examines the role of female impersonators (transvestites in western terminology), and transgender dancers, and their associated communities. Kothis are men who often identify themselves as female and perform as dancers, while Hijras are often transgender.

For most dancers of whatever classification, their starting point was often classical Kathak, but their performances – known as ‘Mujra’ – were varied in eroticism or sexual innuendo.

Instead of improving these women’s lives, abolition, in both cases, made them worse, with many drifting into more obvious prostitution and commercial sex work, Morcom argues.

“It was like history repeating itself,” she said.

In the late 19th and early 20 century, the British had launched an anti-nautch (anti-dance) campaign, portraying the ancient and long running courtesan system of female dancers and performing artists, as decadent and wanton and really just a front for prostitution.

“They argued it was ruining the fabric of society and that it was an indignity to womanhood,” explained Morcom.

For her, Bollywood was kinder, than the moral campaigners who won a political victory over these courtesans in colonial India.

Pakeezah, Umrao Jaan, and Devdas, to name just three, were popular characters in their own right and appeared in the films as stunning performers who embodied a certain sense of (tragic) romance and refinement.

“It is very nostalgic – you had these beautiful, suffering women. In “Pazeekah”, the heroine is full of self-loathing; in “Umrao Jaan”, the mother rejects her.”

It was also no surprise that powerful men could be mesmerised and seduced by them, but these heroines were often also troubled and complicated.

These women were by no means perfect and all the more attractive for it, and there was some level of suggested moral ambiguity; and yet the women still possessed a powerful dignity and were accorded a certain respect.

“The moral campaign against them was started by the British but was joined by other (Indian) movements. These women lost their work status and their livelihoods. They were performers and were highly skilled. They were earning their own keep and paying taxes.”

The same process also befell the ‘Devadasis’, another ancient and controversial class of female ‘performer’.

Mainly attached to Hindu temples – sometimes being ritually married to them – they enjoyed or endured an ambiguous status as well, but the British and new burgeoning Indian (English-educated) middle-class saw them as prostitutes only.

“They (the devadasis) were like courtesans – they had temple duties, and owned temple property and there was a matrilineal line of inheritance.”

These women would have relationships, albeit outside of conventional structures, but were not engaged in prostitution as we might define it.

“What do you call prostitution?” Asked Morcom. “They had upper caste patrons and had extra-marital relations – it might be only one or a few, but it wasn’t like here’s a Rs100 and you sleep with 10 men in a day, it wasn’t like that. That’s a crucial distinction but the British didn’t understand that.”

Equally, it was not unusual to have men perform the roles of women in some traditions of theatre or dance.

In both Parsi and Maharashtran theatre, there was nothing untoward in men playing or impersonating female roles.

In the courtesan system, gender roles were also more murky and loosely defined.

Morcom recounted travelling to Lucknow and speaking to a group of male dancers/performers there.

“They said: ‘There is no Mujra here…the only Mujra performed is by boys…’ What? My ears almost dropped off,” recalled Morcom.

There was a space where these men could perform and live as they wished. Many marry conventionally but do not always have active heterosexual relations. And some reserve their ultimate love for a man, but are discreet and subtle about it, as Indian law – which changed recently to uphold a ban on gay relations – dictates.

This part of Indian dance culture is extremely complicated and not easy to describe, especially as the law has once again shifted the balance from openness to secrecy and exclusion – alluded to in Morcom’s book subtitled, ‘Cultures of Exclusion‘.

Morcom remembered another meeting in Delhi with a ‘Kothi’, a guy who would dance as a woman.

“He had learnt Kathak and other traditions where boys still perform female roles and someone had maliciously told his parents that he had sex with men.

“They knew he danced as a female but had not associated this with anything to do with his sexuality but when they were told, they went crazy, burnt his dresses and smashed his jewellery, and told him not to dance again. They said it was making him feminine.

“I met lots of lower class boys who live in that world and lead double lives.”

Her argument is that abolishing the courtesan system and the dance bars made matters worse for many women (and some men) engaged in those systems.

Some murja does take still take place in private homes, but Indian obscenity laws can be used to prosecute those who patronise it and it is said to also occur in Pakistan, but Morcom has only looked at mujra in relation to India.

Morcom believes traditional gender roles allowed for a degree of diversity of performers.

In addition to courtesans, there were transvestites and transgender performers. They were accepted and their roles within the tradition were recognised and respected and they were not harassed or susceptible to violence in the way they might be now – and that performing and dancing offered them a way out and acceptance.

In the book, she explores this in through and exacting detail, exposing a culture that was both rich and diverse, but also deeply embedded in a wider frame of ambiguity and taboo around sexual relations.

Image: Aishwarya Rai Bachchan as Umrao Jaan

*“Illicit Worlds of Indian Dance”, Anna Morcom, C Hurst and Co, http://www.hurstpublishers.com/book/illicit-worlds-of-indian-dance/